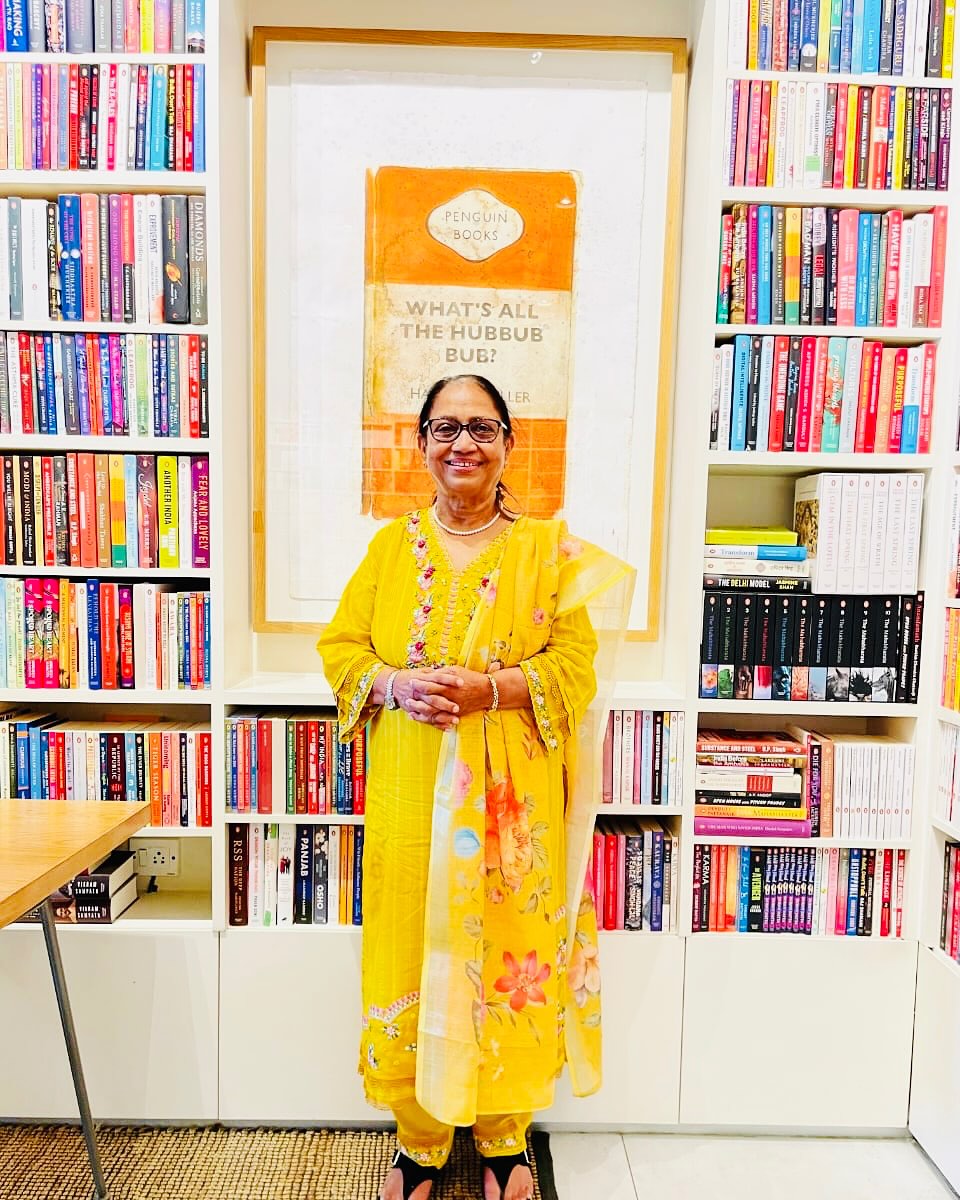

This is the inspiring journey of Banu Mushtaq, the Kannada writer, activist, and lawyer who made history with her International Booker Prize win.

Table Of Contents

Banu Mushtaq

Hello, dear readers!

Welcome to another insightful piece from THOUSIF Inc. – INDIA, where we love bringing you stories of remarkable people who shape our world in quiet yet powerful ways.

Today, we are excited to share the story of Banu Mushtaq, a name that’s been lighting up literary circles lately.

If you enjoy tales of resilience, creativity, and social change, you are in for a treat.

Banu is not just a writer but a beacon of hope for many, especially women in India facing everyday battles.

Born in the lush landscapes of Karnataka, Banu Mushtaq has worn many hats over her 77 years – writer, activist, lawyer, and even journalist.

However, winning the International Booker Prize in 2025 for her collection of short stories, “Heart Lamp, ” really put her on the global map.”

This was a personal victory and the first time a Kannada-language author claimed this prestigious award.

Imagine that – a language spoken by millions in southern India finally getting its due on the world stage.

In this blog post, we will explore her life from her humble beginnings to her groundbreaking achievements, all while keeping things simple and relatable.

We will weave some fascinating details about her world, struggles, and triumphs, so stick around!

As we dive in, remember that Banu’s story is not just about awards or books.

It is about a woman who dared to challenge norms in a society often bound by tradition.

Her words have touched hearts, sparked conversations, and inspired change.

Whether you are a book lover, a history buff, or just curious about strong women making waves, there is something here for you.

Let us start at the beginning, shall we?

Early Life: Roots In Hassan And A Thirst For Knowledge

Picture this: It is 1948 in Hassan, a small town in Karnataka, when India still found its feet after independence.

That is when Banu Mushtaq entered the world, born into a Muslim family on April 3rd.

Life in those days was simple, with rolling hills, coffee plantations, and a close-knit community.

However, for young Banu, the world was full of questions and possibilities.

At just eight years old, her family made a bold move.

They enrolled her in a Kannada-language missionary school in Shivamogga, about 100 kilometers away.

Now, Kannada is the main language of Karnataka, but back then, not everyone in her community prioritized formal education for girls, especially in a new tongue.

The school had a condition: she had to learn to read and write Kannada within six months.

Can you imagine the pressure on a little girl?

However, Banu did not just meet the challenge – she soared past it.

Within months, she was not only reading but starting to write her own thoughts.

This early literacy spark would become the foundation of her lifelong passion for words.

Growing up in a Muslim household in post-independence India meant navigating a blend of cultures.

Karnataka’s society was and still is a mix of Hindu, Muslim, and other traditions, with syncretic practices where people from different faiths shared spaces like shrines.

Banu absorbed these influences, which later showed up in her writing about unity and against division.

Her family valued education, bucking trends where girls might be married off young.

Instead, Banu pursued her studies with vigor, setting the stage for a life of independence.

Education in 1950s Karnataka was not easy.

Schools were often basic, with limited resources, especially in rural areas.

However, Banu’s determination shone through.

She learned Kannada fluently, along with Hindi, Dakhni Urdu (a dialect spoken by many Muslims in southern India), and English.

These languages opened doors to wider worlds, books, newspapers, and ideas from India and beyond.

By her teens, she had thought deeply about society’s inequalities, especially for women.

Little did she know that these early experiences would fuel her future as an activist and storyteller.

As she grew older, Banu faced the typical pressures of her community.

Early marriage was expected, but she chose differently.

At 26, she married for love, a radical act in those times when arranged marriages were the norm.

This choice reflected her emerging spirit of rebellion that would define her career.

Soon after, motherhood brought new joys and challenges, including postpartum depression, which hit her hard at 29.

It was during this tough period that she turned to writing as a way to process her emotions.

What started as personal journaling evolved into powerful stories that captured the essence of women’s lives.

The Bandaya Sahitya Movement: Where Rebellion Meets Literature

To truly understand Banu Mushtaq, we must discuss the Bandaya Sahitya movement, a pivotal chapter in Kannada literature.

“Bandaya” means “rebel” or “rebellion” in Kannada, and this movement erupted in the 1970s like a storm against social injustices.

Karnataka in the ’70s was buzzing with change – India’s emergency period under Indira Gandhi, rising awareness of caste discrimination, and calls for equality.

Writers, poets, and thinkers came together to challenge the status quo through their words.

The Bandaya movement was inspired by progressive ideas, drawing from Marxist thoughts, Dalit (oppressed castes) voices, and feminist perspectives.

It was not about flowery poetry or elite tales; it was raw, real, and aimed at the heart of society’s problems: casteism, poverty, gender inequality, and religious fundamentalism.

Think of it as literature with a purpose: to awaken people and push for change.

Key figures like Poornachandra Tejaswi and K. Satyanarayana led the charge, but it opened doors for underrepresented voices, including women and minorities.

Banu emerged right in the thick of this.

Starting her writing career in the late ’70s, she found a home in Bandaya’s rebellious spirit.

Her stories did not shy away from tough topics.

Instead, they highlighted the struggles of ordinary people, especially women in Muslim communities.

As part of this movement, she joined a wave of Dalit and progressive writers who made Kannada literature more inclusive.

Before Bandaya, much of Kannada writing was dominated by upper-caste narratives.

However, this shift brought diverse perspectives, making the tradition richer and more holistic.

For Banu, Bandaya was not just a style but a lifeline.

It allowed her to blend her personal experiences with broader social critiques.

Her involvement helped pave the way for future generations, showing that literature could be a tool for activism.

Even in 2025, the movement’s echoes are felt in contemporary Kannada works, influencing everything from novels to films.

Banu’s place in it underscores her as a pioneer, using simple language to tackle complex issues.

Career As A Writer: From Personal Stories To Global Recognition

Banu’s writing journey is a testament to how personal pain can birth universal art.

After battling postpartum depression, she poured her heart into short stories that captured the quiet strength of women.

Over the decades, from 1990 to 2023, she published six short story collections, one novel, one essay collection, and one poetry collection.

Her works are mostly in Kannada but have been translated into Urdu, Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam, and English, reaching wider audiences.

One standout story is “Karinaagaragalu,” which inspired the 2003 Kannada film “Hasina” directed by Girish Kasaravalli.

Like her writing, the film delves into themes of identity, resilience, and societal pressures on women.

Banu’s style is straightforward – no fancy words or convoluted plots.

She focuses on everyday lives: a mother navigating family expectations, a girl fighting for education, or a woman challenging religious norms.

Her characters feel real, like neighbors you might chat with over tea.

In 2013, she released a compilation called “Hasīna mattu itara kathegaḷu” (Haseena and Other Stories), which showcased her knack for blending emotion with social commentary.

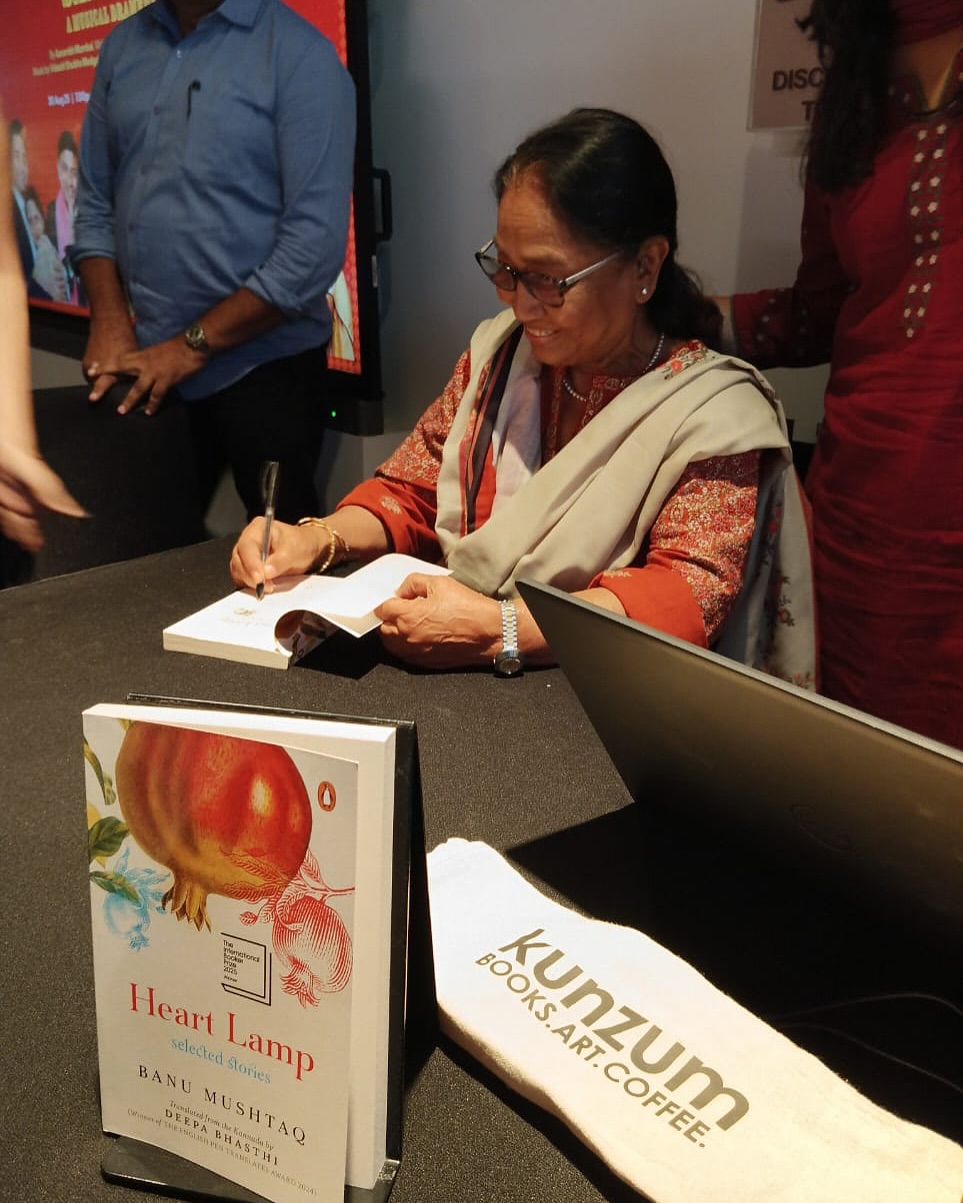

However, her big breakthrough came in 2025 with “Heart Lamp: Selected Stories.”

This English translation by Deepa Bhasthi brought together twelve of her finest tales.

The book explores women’s rights, resistance to caste and religious injustice, and the beauty in ordinary moments.

Judges at the International Booker Prize praised it for its “beautiful accounts of everyday life,” noting how it balances quiet introspection with subtle humor.

Winning the Booker was historic. Not only was Banu the first Kannada writer to win, but “Heart Lamp” was the first short story collection to take the prize.

Deepa Bhasthi became the first Indian translator to win, too.

The award, announced on May 21st, 2025, in London, was worth £50,000, which was shared between the author and translator.

Banu, at 77, reflected humbly: “A story born under a banyan tree in my village can cast its shadow across the world.”

This win spotlighted Kannada literature globally, encouraging more translations and recognition for regional languages.

However, Banu’s writing is not just about acclaim; it is impactful.

Her stories have sparked discussions in schools, women’s groups, and literary festivals.

They empower readers to question inequalities and find strength in their own lives.

In a world of fast-paced thrillers, her gentle yet piercing narratives remind us of the power of simplicity.

A Closer Look At Her Notable Works

To give you a better sense, here is a table summarizing some key aspects of her bibliography based on her known publications:

| Type | Title | Year | Key | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Story Collections | Hasīna mattu itara kathegaḷu (Haseena and Other Stories) | 1990-2013 | Women’s struggles, family dynamics, and social justice | Adapted into the film “Hasina” (2003) |

| Novel | (Untitled in public records, but focuses on personal growth) | Mid-2000s | Identity and resilience | Translated into multiple languages |

| Essay Collection | Reflections on activism and literature | 2010s | Feminism, anti-fundamentalism | Used in academic discussions |

| Poetry Collection | Poetic explorations of everyday life | 2020s | Emotion, nature, human connections | Praised for lyrical simplicity |

| Selected Stories (English) | Heart Lamp | 2025 | Resistance to injustice, women’s rights | Won the International Booker Prize |

This table highlights how her output spans genres, always circling back to themes of empowerment.

While not all titles are widely listed in English, her body of work shows consistency in voice and purpose.

Activism And Legal Career: Fighting On The Frontlines

Banu Mushtaq’s pen is mighty, but her actions speak even louder.

Since the 1980s, she has been a fierce activist in Karnataka, tackling fundamentalism and social injustices head-on.

As a lawyer, she used her skills to advocate for the marginalized, blending law with literature for greater impact.

One of her boldest stands came in 2000 when she fought for Muslim women’s right to enter mosques.

In many conservative circles, women were barred from praying in the main prayer halls. Banu argued it was a denial of equality.

For this, she faced a three-month social boycott from her community, menacing phone calls, and even an attempted stabbing, thankfully stopped by her husband.

These threats did not deter her; they fueled her resolve.

In the early 2000s, she joined the Komu Souhardha Vedike, a forum promoting communal harmony.

They protested against groups trying to block Muslims from the Baba Budangiri shrine in the Chikmagalur district.

This site, sacred to both Hindus and Muslims, symbolizes India’s syncretic culture.

Banu’s involvement highlighted her commitment to unity over division.

More recently, in 2022, she supported Muslim students’ right to wear hijab in schools during Karnataka’s heated controversy.

She saw it as a personal choice and religious freedom, not coercion.

Her stance drew praise and criticism, but she stood firm, drawing from her experiences as a Muslim woman in a diverse society.

Banu’s journalism career amplified her activism.

She reported for “Lankesh Patrike,” a progressive newspaper known for bold takes on social issues, and briefly for All India Radio in Bengaluru.

Her articles exposed inequalities, much like her stories do.

Her multifaceted career as a writer, lawyer, activist, and journalist shows how one can wear many roles to drive change.

In India’s context, where Muslim women often face double discrimination (gender and religion), Banu’s work is vital.

She challenges patriarchal norms within her community while fighting broader societal biases.

Her efforts have inspired women’s groups and influenced policy discussions on gender and religion.

The International Booker Prize: A Milestone For Kannada Literature

Let us zoom in on that 2025 win – it is a game-changer.

The International Booker Prize honors fiction translated into English, sharing the prize money between author and translator.

Banu’s “Heart Lamp” beat out strong contenders worldwide, announced at a glittering ceremony in London.

The book itself is a gem.

Its twelve stories span over 30 years of her writing, each one a “lamp” illuminating hidden corners of life.

Themes range from patriarchal oppression to quiet acts of rebellion.

One story might follow a young bride navigating in-law expectations; another could explore a woman’s quest for education amid poverty.

Deepa Bhasthi’s translation captures Kannada’s nuances, making it accessible yet authentic.

Judges called it a “wonderful collection” with a “consistent vision.”

The Guardian reviewed it positively, noting its mix of tones – from serene to comedic.

This win is huge for Kannada literature. Kannada has a rich history, from ancient poets like Pampa to modern giants like U.R. Ananthamurthy.

However, global recognition has been limited due to fewer translations.

Banu’s success could spark more interest, funding, and opportunities for regional writers.

After her win, Banu has been in the spotlight, interviewed, and featured in festivals, and there have even been talks of film adaptations.

At 77, she is proof that age is no barrier to impact.

Her message?

Stories matter, no matter how small they seem.

Influence And Legacy: Inspiring The Next Generation

Banu Mushtaq’s influence ripples far beyond bookshelves.

In Karnataka, she is a role model for aspiring writers, especially women from minority backgrounds.

Her work has been taught in universities, sparking debates on feminism in Indian literature.

Groups like women’s NGOs use her stories in workshops to discuss rights and empowerment.

On a broader scale, she contributes to India’s feminist movement.

Think of icons like Ismat Chughtai or Mahasweta Devi – Banu fits right in, focusing on marginalized voices.

Her activism has helped shift attitudes toward more inclusive practices in religious and social spaces, even if slowly.

In 2025, with rising debates on women’s rights and communal harmony, Banu’s voice is timelier than ever.

She reminds us that change starts with empathy and storytelling.

Young writers today credit her for showing that regional languages can go global.

Trivia Time: An Interesting Fact

Did you know Banu Mushtaq once thwarted an attempted attack during her activism? In 2000, while advocating for women’s mosque access, an assailant tried to stab her, but her husband intervened just in time. This close call only strengthened her resolve, turning a scary moment into fuel for her lifelong fight against injustice. It is a reminder of the real risks activists face, yet how perseverance wins out.

Challenges Faced: Navigating Personal And Professional Hurdles

No story of triumph is without obstacles.

Banu faced plenty of community backlash for personal health struggles.

Postpartum depression in the ’70s was not widely discussed, especially in conservative families.

She channeled that pain into writing, but it took courage to share such vulnerabilities.

Professionally, as a woman in law and activism, she encountered skepticism.

In male-dominated courtrooms, her voice for women’s rights often met resistance.

The 2000 boycott isolated her socially, making everyday life tough.

However, she persisted, supported by her family and like-minded allies.

In literature, getting published as a progressive writer was not easy.

Bandaya’s works sometimes faced censorship or low sales, but Banu’s authenticity won readers over.

Today, she reflects on these as growth opportunities, advising young people to “Face fears with words and actions.”

Broader Context: Women in Indian Literature And Activism

Banu’s story fits into a larger tapestry of Indian women breaking barriers.

From Arundhati Roy’s Booker win in 1997 to Geetanjali Shree’s in 2022, women are claiming space in global lit.

However, regional languages like Kannada need more spotlight. Banu’s win bridges that gap.

Activism-wise, she is part of a lineage that includes figures like Savitribai Phule, who fought for girls’ education, and modern activists like Aruna Roy.

Women like Asma Jahangir (from Pakistan) in Muslim communities inspire similar fights.

Banu adds a southern Indian flavor, emphasizing local issues like hijab rights or shrine access.

India’s diversity means activism varies by region.

Banu found fertile ground in Karnataka with its history of progressive movements (like the Lingayat reforms).

Her work encourages cross-cultural dialogues, showing how shared struggles unite us.

Personal Reflections: What Makes Banu Tick

From interviews, Banu comes across as warm and grounded.

She loves nature, perhaps from her Hassan roots, and often draws inspiration from village life.

Family is central; her love marriage and supportive husband were key to her freedom.

She believes in education’s power, often saying, “Knowledge is the true lamp that lights the heart.”

Her multilingual skills help her connect with diverse audiences.

In her free time, she enjoys reading classics and mentoring young writers.

The Future: What Is Next For Banu And Kannada Lit

At 77, Banu shows no signs of slowing.

There are whispers of more translations, perhaps her novel or essays.

She might write a memoir, sharing activism tales.

For Kannada literature, her win could lead to more funding for translations, festivals, and international exchanges.

Young writers are already following her path, blending social issues with storytelling.

Organizations like the Karnataka Sahitya Academy, which awarded her earlier, continue supporting such talents.

Conclusion: A Lamp That Continues To Shine

As we wrap up this deep dive into Banu Mushtaq’s world, we hope you have felt the warmth of her “heart lamp.”

From a curious girl in Hassan to a global literary star, her journey inspires us to chase dreams, challenge wrongs, and tell our stories.

In a world that can feel divided, Banu’s work reminds us of our shared humanity, simple, clear, and profound.

Thank you for reading this piece from THOUSIF Inc. – INDIA.

We are passionate about sharing stories that matter, just like Banu’s.

If you enjoyed this, why not explore more articles on our site?

We’ve got plenty on inspiring figures, cultural insights, and tips for everyday life.

Please comment below with who you would like us to feature next.

Until then, keep shining your own light!