Table Of Contents

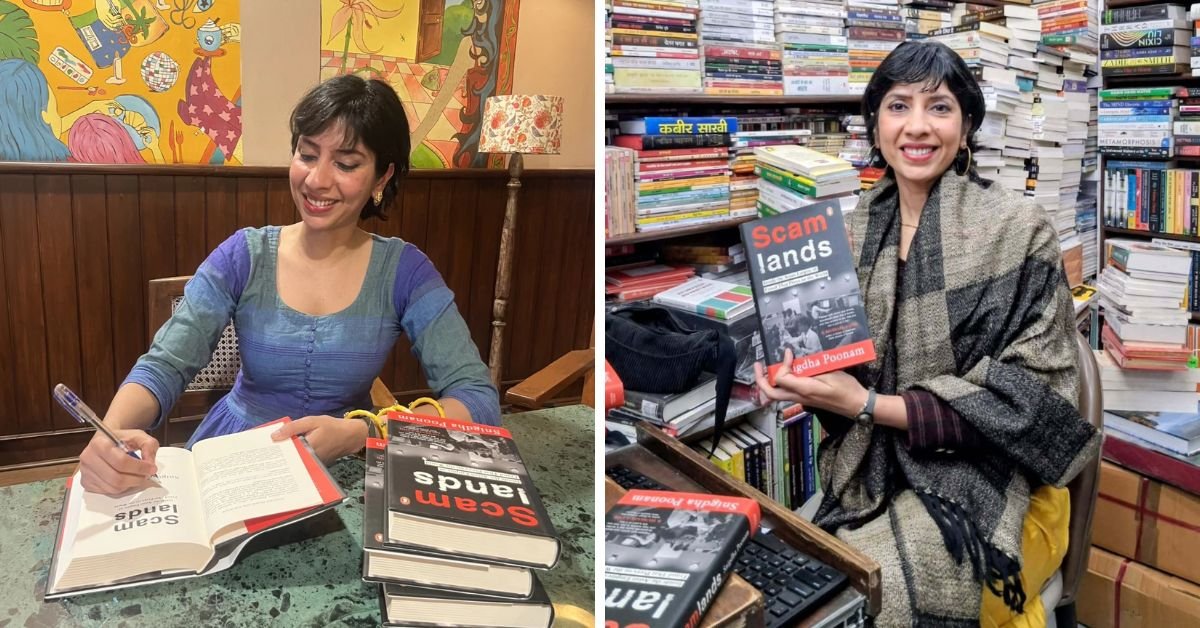

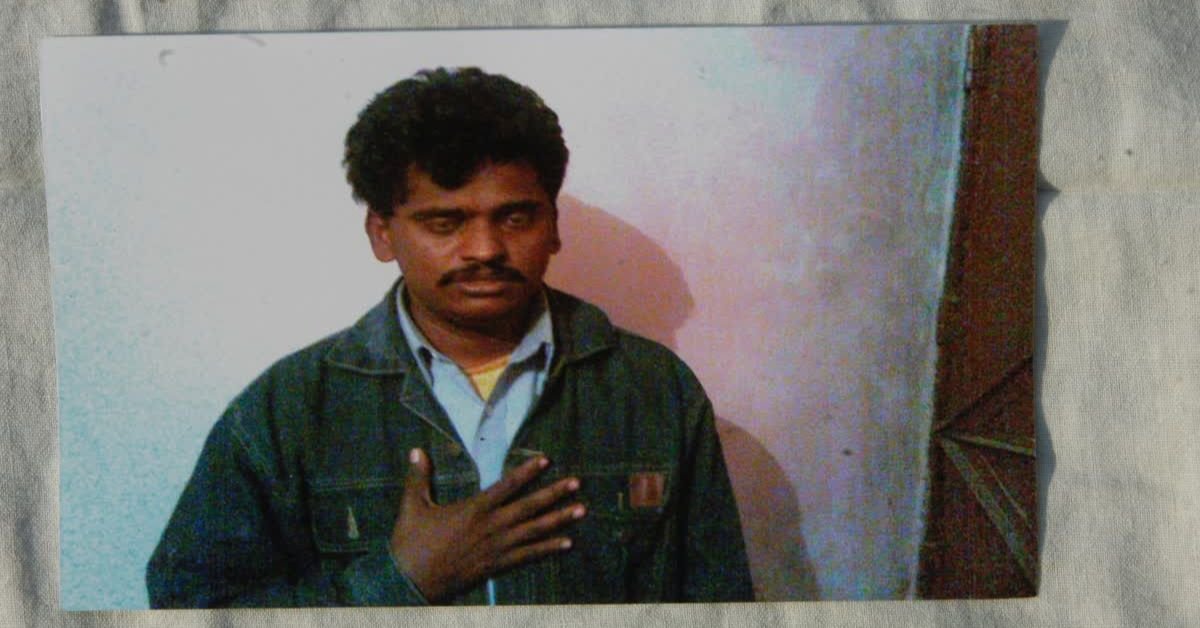

Surendra Koli

In the annals of Indian criminal history, few cases have evoked as much horror, outrage, and debate as the Nithari serial murders.

At the center of this chilling saga stands Surendra Koli, a man whose name became synonymous with unimaginable brutality, yet whose story is also one of legal twists, acquittals, and questions about justice.

Born into poverty in the hills of Uttarakhand, Koli’s journey took him from odd jobs in rural India to the bustling outskirts of Delhi, where he became entangled in one of the country’s most notorious crime investigations.

This biography delves into Koli’s life, drawing from extensive research into his background, the events that unfolded in Nithari village, the grueling legal battles, and his eventual release from prison on November 13, 2025.

We’ll explore the facts with clarity and simplicity, avoiding sensationalism while shedding light on the human elements behind the headlines.

Whether you are familiar with the case or hearing about it for the first time, this account aims to provide a balanced, informative perspective on a man who spent nearly two decades behind bars, only to walk free amid widespread controversy.

Early Life And Background

Surendra Koli, often spelled Surinder Koli in various records, was born in 1970 (though some sources cite 1972) in the small village of Mangrukhal in Almora district, Uttarakhand.

Nestled in the Himalayan foothills, Almora is known for its scenic beauty but also for the economic hardships faced by many of its residents.

Koli grew up in a financially strained family, part of India’s vast rural underclass, where opportunities were scarce and survival often meant hard labor from a young age.

From what we know of his childhood, Koli’s family struggled to make ends meet.

He was one of several siblings, and the household relied on meager earnings from agriculture or manual work.

Education was a luxury; Koli attended school only up to Class VI before dropping out at around age 13 to contribute to the family’s income.

This decision was not uncommon in rural India during the 1980s, where child labor was rampant, and formal schooling often took a backseat to immediate needs.

As a teenager, Koli took on various odd jobs to support his family.

Reports suggest he worked in animal skinning, a gritty occupation that involved handling raw flesh, experiences that later fueled speculation about his psychological makeup.

Some accounts mention he developed a habit of eating raw meat during this time, though these details remain anecdotal and unverified in official records.

What is clear is that life in Mangrukhal offered little in the way of advancement, prompting Koli to seek better prospects elsewhere.

In his late teens or early twenties, Koli migrated to Delhi, a common path for many from Uttarakhand seeking urban employment.

The bustling capital promised jobs, but for someone with limited education and skills, the reality was menial labor.

He started by washing utensils at a rundown hotel in New Delhi, earning a pittance but gaining a foothold in the city.

This period marked the beginning of his independence, away from the familial ties of his village.

Koli’s work ethic led him to more stable positions.

From 1993 to 1998, he served as a cook at the home of a retired brigadier in Noida, a satellite city of Delhi that was rapidly developing into a hub for middle-class families and businesses.

This job provided him with valuable experience in domestic service, a field where reliability could lead to better opportunities.

In 1998, at around age 28, Koli married a woman named Shanti.

However, the marriage was short-lived; he left her soon after and returned to Noida, leaving behind a young daughter named Simran, who was about three years old when the Nithari events unfolded years later.

By the early 2000s, Koli had secured another role as domestic help, this time at the residence of a retired army major, where he worked for six years.

These jobs honed his skills in household management, but they also exposed him to the stark class divides of urban India.

In 2004, he joined the household of businessman Moninder Singh Pandher at D-5, Sector-31, Noida, a move that would irrevocably change his life.

To better understand Koli’s early years, consider the socio-economic context of Uttarakhand in the 1970s and 1980s.

The region, then part of Uttar Pradesh, faced high poverty rates, with many families migrating for work.

Koli’s story mirrors thousands of others: a quest for stability amid systemic challenges.

However, these humble beginnings offer little clue to the horrors that would later be associated with his name.

Arrival In Noida And Employment With Pandher

Noida, short for New Okhla Industrial Development Authority, emerged in the late 20th century as a planned city to decongest Delhi.

By the time Koli arrived, it was a mix of affluent sectors and impoverished villages like Nithari, where migrant workers lived in shanties alongside upscale bungalows.

Sector-31, where Pandher’s house stood, was a middle-class enclave.

However, the adjacent Nithari village was home to daily wage earners, many from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, whose children often roamed unsupervised.

Moninder Singh Pandher, a wealthy businessman with interests in construction and other ventures, hired Koli around 2004 as a full-time servant.

Pandher’s home, D-5, was a spacious bungalow with modern amenities, a far cry from Koli’s rural roots.

Koli’s duties included cooking, cleaning, and general maintenance.

By all accounts, he was diligent and unassuming, blending into the background of domestic life.

During this period, Koli lived on the premises, which gave him autonomy when Pandher was away on business trips.

Pandher, a widower with adult children living abroad, often traveled, leaving Koli in charge.

This setup, in hindsight, provided the isolation that investigators later linked to the alleged crimes.

Koli maintained contact with his family in Uttarakhand, sending money home, but his life in Noida was largely solitary.

Life in Nithari village was a stark contrast to the bungalow’s comfort.

The area was plagued by poverty, with children from migrant families vulnerable to exploitation.

Reports from the time describe Nithari as a place where disappearances went unnoticed due to police apathy and community fragmentation.

Koli, as a local fixture, was known to some residents, but no red flags were raised until much later.

The Alleged Crimes: What Happened?

The Nithari serial murders, spanning from 2005 to 2006, involved the disappearance and killing of at least 19 individuals, primarily young girls from low-income families in the village.

According to initial confessions and investigations, victims were lured to Pandher’s house, sexually assaulted, strangled, and dismembered.

Body parts were disposed of in drains and polythene bags behind the property.

Koli was accused of being the primary perpetrator, confessing to killing six children and one adult woman named Payal (a 20-year-old sex worker) after assaulting them.

He described using sweets or chocolates to entice children, then strangling them with their own clothing.

Post-mortem acts reportedly included necrophilia and cannibalism, with Koli admitting to consuming organs like livers.

The dismemberment was done with “butcher-like precision,” using tools like saws, and the remains were scattered to avoid detection.

Victims ranged in age from 3 to 12 for children, mostly girls (11 out of 17 identified skeletons were female).

The adult victim, Payal, disappeared after being called to the house; her cellphone was used by Koli afterward, providing a key lead.

Motives cited included sexual frustration and impotence, with Koli claiming he acted alone during Pandher’s absences.

The crimes went undetected for months due to police inaction on missing persons reports from low-income families.

It was not until December 2006 that the truth began to emerge, when parents of missing children pointed fingers at Koli and the house.

Known Victims And Details

This table highlights the tragic scale, focusing on confirmed cases from court records.

| Victim | Age | Disappearance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rimpa Haldar | 14 | February 8, 2005 | First convicted case: raped and murdered. |

| Arti Prasad | 7 | October 25, 2006 | Strangled and dismembered. |

| Rachna Lal | 9 | April 10, 2006 | Lured with sweets. |

| Deepali Sarkar | 12 | June 2006 | Identified by belongings. |

| Chhoti Kavita | 5 | June 4, 2005 | One of the youngest victims. |

| Payal (Deepika) | 20-26 | May 2006 | Adult victim; cellphone traced. |

| Others (unlisted) | 3-12 | 2005-2006 | Total 19+ suspected; many unidentified. |

Discovery And Investigation

The breakthrough came in December 2006 when two Nithari residents, suspecting Koli in their daughters’ disappearances, searched a water tank behind D-5 and found a decomposed hand.

They alerted authorities via the Resident Welfare Association president.

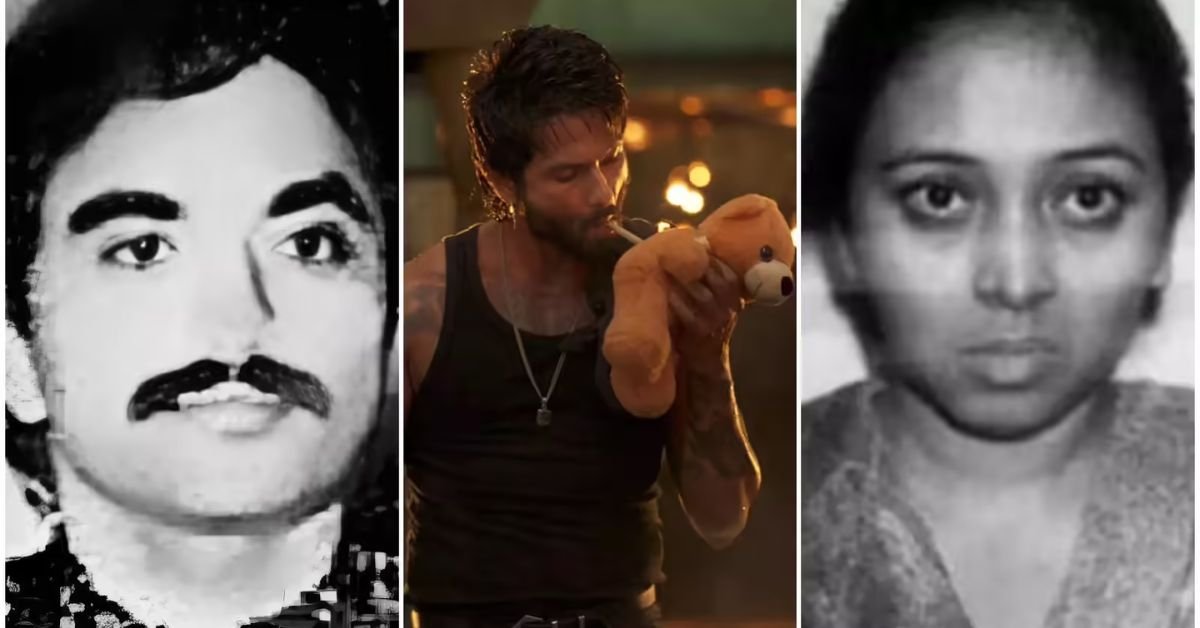

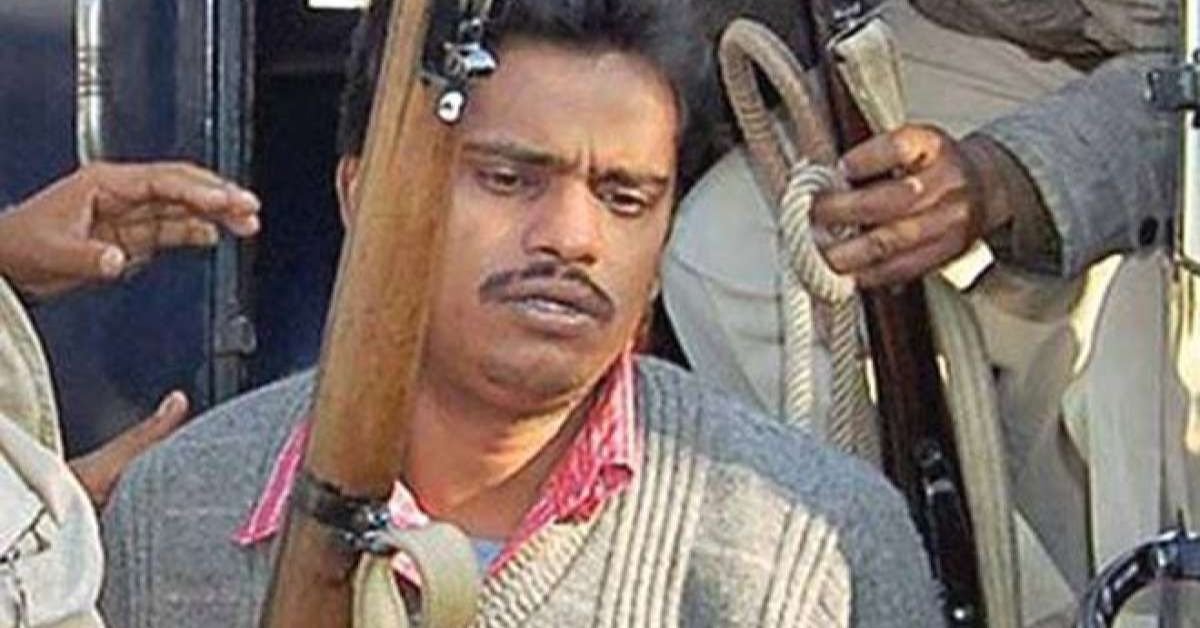

On December 26, Pandher was arrested for Payal’s murder; Koli followed on December 27 under the alias Satish.

Digs uncovered skeletal remains, skulls, and body parts in drains and bags.

By January 2007, 17 skeletons were found (later 19 skulls), with 15 identified via photos, belongings, and DNA tests at Hyderabad’s Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics.

Forensics at AIIMS revealed strangulation, rape, and dismemberment.

Initial police response was criticized for negligence; families accused corruption.

Two officers were suspended, six dismissed.

The central government formed a committee led by Manjula Krishnan, indicting Uttar Pradesh Police for lapses.

No evidence of organ trade emerged, despite suspicions from missing torsos.

On January 9-11, 2007, the case transferred to the CBI. Koli underwent brain mapping, polygraph, and narco-analysis in Gandhinagar, confirming confessions.

CBI ruled Koli a psychopath, giving Pandher a clean chit. Raids on Pandher’s properties and a local doctor yielded nothing.

Confessions And Forensic Tests

Koli’s confessions were graphic and detailed, given during custody.

He described the modus operandi: luring, assault, killing to silence victims, dismembering in his washroom, and disposal.

He claimed no remorse but showed emotion for his daughter.

Under narco-analysis (truth serum), he reiterated details, including cannibalism.

Forensic evidence included bloodstains, tools, and DNA matches.

However, courts later questioned the confessions’ validity, citing possible coercion and lack of corroboration.

Polygraph tests indicated deception on some points, but overall supported his involvement.

Trials And Convictions

Trials began in Ghaziabad’s special CBI court.

On February 12, 2009, Koli and Pandher were convicted in Rimpa Haldar’s case, sentenced to death as “rarest of rare.”

Koli received multiple death sentences: May 2010 for Arti Prasad, September 2010 for Rachna Lal, December 2010 for Deepali Sarkar, and more up to 2017, totaling 13.

Pandher was convicted in two but acquitted on appeal. Koli’s sentences were upheld initially by higher courts.

Timeline Of Key Legal Events

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| February 2009 | First conviction and death sentence for Rimpa Haldar. |

| May 2010 | Death for Arti Prasad. |

| September 2010 | Death for Rachna Lal. |

| December 2010 | Death for Deepali Sarkar. |

| 2011 | Supreme Court upholds one conviction. |

| July 2014 | Mercy petition rejected by the President. |

| September 2014 | Execution stayed by the Supreme Court. |

| January 2015 | Allahabad HC commutes to life in one case. |

| October 2023 | Allahabad HC acquits in 12 cases. |

| July 2025 | SC upholds acquittals in 12 cases. |

| November 2025 | SC acquits in final case; release ordered. |

Appeals And Acquittals

Appeals began in 2009, with Allahabad High Court acquitting Pandher but upholding Koli’s sentence.

The Supreme Court upheld the decision in 2011, but stayed the execution in 2014 due to delays.

In 2015, one death sentence was commuted to life.

The turning point came in October 2023: Allahabad HC acquitted both in all cases, citing shoddy investigation, unreliable evidence, and failure to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

The court called it a “betrayal of public trust.” In July 2025, SC upheld 12 acquittals; on November 11, 2025, it acquitted in the last case, ordering immediate release, noting a miscarriage of justice.

Life Behind Bars

Koli spent 19 years in prison, mostly on death row in Dasna and Meerut jails.

Initially volatile, he later turned introspective, reciting Hanuman Chalisa and reading religious books.

Correctional officers noted his calm demeanor and adherence to Hindu rituals.

He maintained innocence in later years, focusing on family.

The psychological toll was immense; repeated death sentences and stays created a “rollercoaster” of emotions, highlighting issues with capital punishment delays.

Release And Aftermath

On November 13, 2025, Koli walked free from jail, a free man after nearly two decades.

The release sparked mixed reactions: relief for his family, outrage from victims’ kin who felt justice was denied.

Koli plans to return to Uttarakhand, but his future remains uncertain amid public scrutiny.

Psychological Profile

Though a full psychological report is not publicly detailed, CBI interrogators labeled Koli a psychopath.

His background of poverty and early labor may have contributed to detachment.

Confessions suggested deep-seated issues, possibly from sexual frustrations.

No formal diagnosis of mental illness was used in defense, but the case raised questions about profiling serial offenders in India.

Controversies And Public Opinion

The case exposed police bias against the poor, with initial dismissals of missing reports as “runaways.”

Media sensationalism amplified cannibalism rumors, dubbing Koli the “Nithari Monster.”

Class dynamics played a role: Pandher, wealthy, received leniency; Koli, a Dalit worker, bore the brunt.

Acquittals fueled debates on evidence standards in circumstantial cases.

Impact On Society And Law

Nithari prompted reforms in missing persons protocols and child protection.

It highlighted vulnerabilities of migrant communities and led to compensation for families (Rs. 12 lakhs each, though some rejected it).

Legally, it underscored the need for robust investigations to avoid wrongful convictions.

Trivia

Interestingly, despite the gruesome accusations, Koli was known in prison for his devotion, often reciting Hindu hymns like the Hanuman Chalisa, a stark contrast to his alleged persona.

Conclusion

Surendra Koli’s life is a complex tapestry of poverty, accusation, endurance, and redemption through the courts.

From a village boy to a figure of national infamy and back to freedom, his story reminds us of the fallibility of justice systems and the human cost of errors.

While the Nithari victims’ families continue seeking closure, Koli’s acquittal closes a dark chapter.

We hope this biography has provided insight into this pivotal case.

If you are interested in more true crime stories or biographies of intriguing figures, explore our other articles on the website.

There is always more to discover!